“The goal isn’t more agents. It’s agents that work together.”

The Organizational Challenge

When you start building AI agents, things tend to get chaotic fast. Your first agent works beautifully in isolation. Then you build a second one, and they start stepping on each other’s toes. By the time you have five or six agents running, you’re facing a mess: agents duplicating work, overwriting each other’s outputs, losing context, and generally creating more problems than they solve.

This isn’t a technology problem—it’s an organizational problem. Just like human teams need structure to collaborate effectively, AI agents need clear roles, responsibilities, and boundaries to work together without chaos.

We needed a structure. So we built squads.

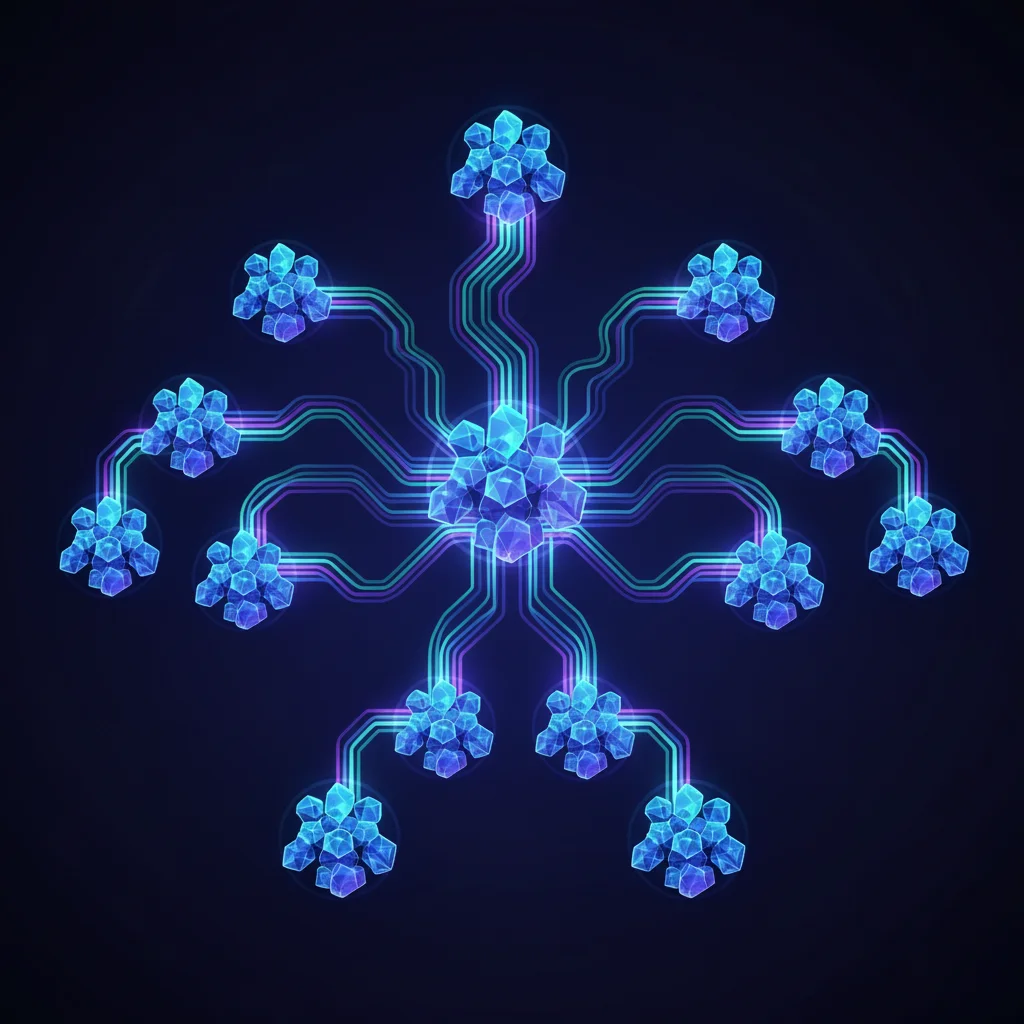

What Exactly Is a Squad?

A squad is a domain-aligned team of AI agents. Think of it like a department in a company, but staffed by AI agents instead of humans.

Every squad has four defining characteristics. First, it owns a domain—a specific area of responsibility like finance, engineering, or customer relations. Second, it produces outputs—each squad writes to specific directories or repositories that it controls. Third, it maintains memory—context persists across sessions so the squad can build on previous work. Fourth, it executes autonomously—squads can be triggered manually, on schedules, or by events.

The simplest way to think about it: a squad combines a domain, a set of specialized agents, shared memory, and defined outputs.

Our Squad Structure in Practice

Here’s how we organize our own agent infrastructure:

agents-squads/

├── hq/ # Headquarters (orchestration)

│ └── .agents/squads/ # Squad definitions

├── company/ # Company squad outputs

├── product/ # Product squad outputs

├── engineering/ # Engineering squad outputs

├── research/ # Research squad outputs

├── intelligence/ # Intelligence squad outputs

├── customer/ # Customer squad outputs

├── finance/ # Finance squad outputs

└── agents-squads-web/ # Website squad outputsEach squad owns its output directory. When the finance squad produces a cost report, it goes in the finance directory. When the research squad writes analysis, it goes in research. There’s never ambiguity about who owns what or where things belong.

Defining a Squad

Squads are defined in simple configuration files. No complex infrastructure required—just YAML and markdown:

# .agents/squads/finance/SQUAD.md

name: finance

mission: Financial operations and analysis

memory: .agents/memory/finance/

outputs: ../finance/

agents:

- cost-tracker

- budget-analyzer

- invoice-processorThis definition tells the system everything it needs to know: which domain the squad covers, where its memory lives, where it writes outputs, and which agents belong to it.

Defining an Agent

Each agent within a squad is a markdown file that specifies what the agent does and how:

# .agents/squads/finance/cost-tracker.md

## Purpose

Track and analyze AI costs across all squads.

## Inputs

- Langfuse telemetry data

- Budget thresholds from memory

## Outputs

- Cost reports in ../finance/costs/

- Alerts when thresholds exceeded

## Instructions

1. Query Langfuse for recent executions

2. Calculate costs by squad and agent

3. Compare against budgets

4. Generate report and alertsThat’s it. Agents are prompts with structure. When you trigger the cost-tracker agent, Claude Code receives these instructions along with the squad’s memory and executes accordingly.

Why This Architecture Works

We’ve found several benefits from organizing agents into squads.

Clear ownership eliminates ambiguity. When someone asks “where do cost reports go?”, the answer is always the same: the finance directory, owned by the finance squad. There’s never confusion about which agent should handle a task or where outputs should land.

Domain expertise develops naturally. Agents within a squad share context about their domain. The finance squad accumulates knowledge about budgets, cost patterns, and financial processes. The engineering squad develops expertise in code, systems, and infrastructure. Each squad becomes increasingly capable in its area over time.

Memory stays focused. Each squad has its own memory space, which means finance knowledge doesn’t pollute engineering context and vice versa. When the cost-tracker agent runs, it gets finance-relevant context—not irrelevant information about code reviews or customer outreach.

Squads can compose together. Different squads can trigger each other, creating workflows that span domains. The intelligence squad might discover an opportunity, which triggers the customer squad to generate outreach, which triggers the finance squad to track associated costs. Each squad handles its piece, and the workflow emerges from their coordination.

How Execution Works

The execution model is straightforward:

Trigger (manual/scheduled/event)

↓

Squad selected

↓

Agent selected (or squad picks)

↓

Claude Code executes agent prompt

↓

Output written to squad directory

↓

Memory updatedYou can trigger a specific agent directly, or you can trigger a squad and let it determine which agent should handle the request. Either way, the agent executes its instructions, produces outputs in the appropriate location, and updates the squad’s memory with anything learned.

What We Learned Building This

Several lessons emerged from building and running this architecture.

Start smaller than you think. We initially created eleven squads. That was too many. The boundaries weren’t clear, squads overlapped, and coordination became complicated. We’ve since consolidated to fewer squads with clearer domains. Our advice: start with three to five squads covering your most important domains, and split later when you have good reason.

Organize by domain, not by task. We made the mistake of creating task-based squads like “email-sender” and “report-writer.” This doesn’t work because tasks cross domains—sometimes you need to send emails about finance, sometimes about engineering. Domain-based organization (finance squad, engineering squad) makes more sense because it groups related expertise together.

Memory is essential. Without persistent memory, every session starts from zero. The cost-tracker agent can’t improve over time because it forgets everything between runs. Squad memory is what enables agents to learn from experience, build on previous work, and develop genuine expertise in their domains.

Outputs define boundaries. If you can’t clearly articulate what a squad outputs, it’s probably not a real squad. The discipline of specifying outputs forces clarity about what each squad actually does. When we found ourselves creating squads without clear outputs, that was a sign we needed to rethink the organization.

If We Started Over

Knowing what we know now, we’d make a few changes.

We’d start with even fewer squads—maybe four or five core domains—and resist the urge to split until the need became obvious. We’d define output schemas more rigorously upfront, specifying not just where outputs go but what format they take. And we’d build better mechanisms for inter-squad communication, which is currently more ad-hoc than we’d like.

Try It Yourself

The pattern is simple enough to implement without any special tooling. Start by defining your domains—what areas of work exist in your organization? Then assign agents to each domain—which specialized agents should handle work in each area? Allocate outputs—where should each domain write its results? And enable memory—how will context persist across sessions?

You don’t need our specific CLI or infrastructure. The pattern works with any orchestration approach. What matters is the organizational structure: clear domains, clear ownership, persistent memory, and defined outputs.

Ready to start? Open your terminal and run:

squads initThis creates the .agents/ directory structure and gets you started with your first squad. Or get the full setup guide.

This is part of the Engineering AI Agents series—practical patterns for building autonomous AI systems.